By Derrick Broze

“The United States is brokering land deals to enrich corporations and deprive the Shoshone of our lawful property rights and interests,†Ian Zabarte, a member of the Western Shoshone nation, says while sitting at his home in the Las Vegas area. Zabarte recently celebrated his 54th birthday and also marked 30 years of defending his community against the controversial Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste site.

Despite having waged this fight for three decades, Zabarte is prepared to continue fighting until his death. His efforts are only the latest in a long history of resistance to nuclear testing and encroachment on native lands. Zabarte says he inherited his defense of the Western Shoshone lands from his grandfather, Raymond Graham, who was a founding member of the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI). Graham was heavily involved in fighting for Shoshone causes until the time of his death, which Zabarte believes was the result of exposure to radiation from the nuclear testing in the area.

Ian Zabarte, principal man of the Western Shoshone Nation, sits at his home in the Las Vegas area. Photo: Derrick Broze

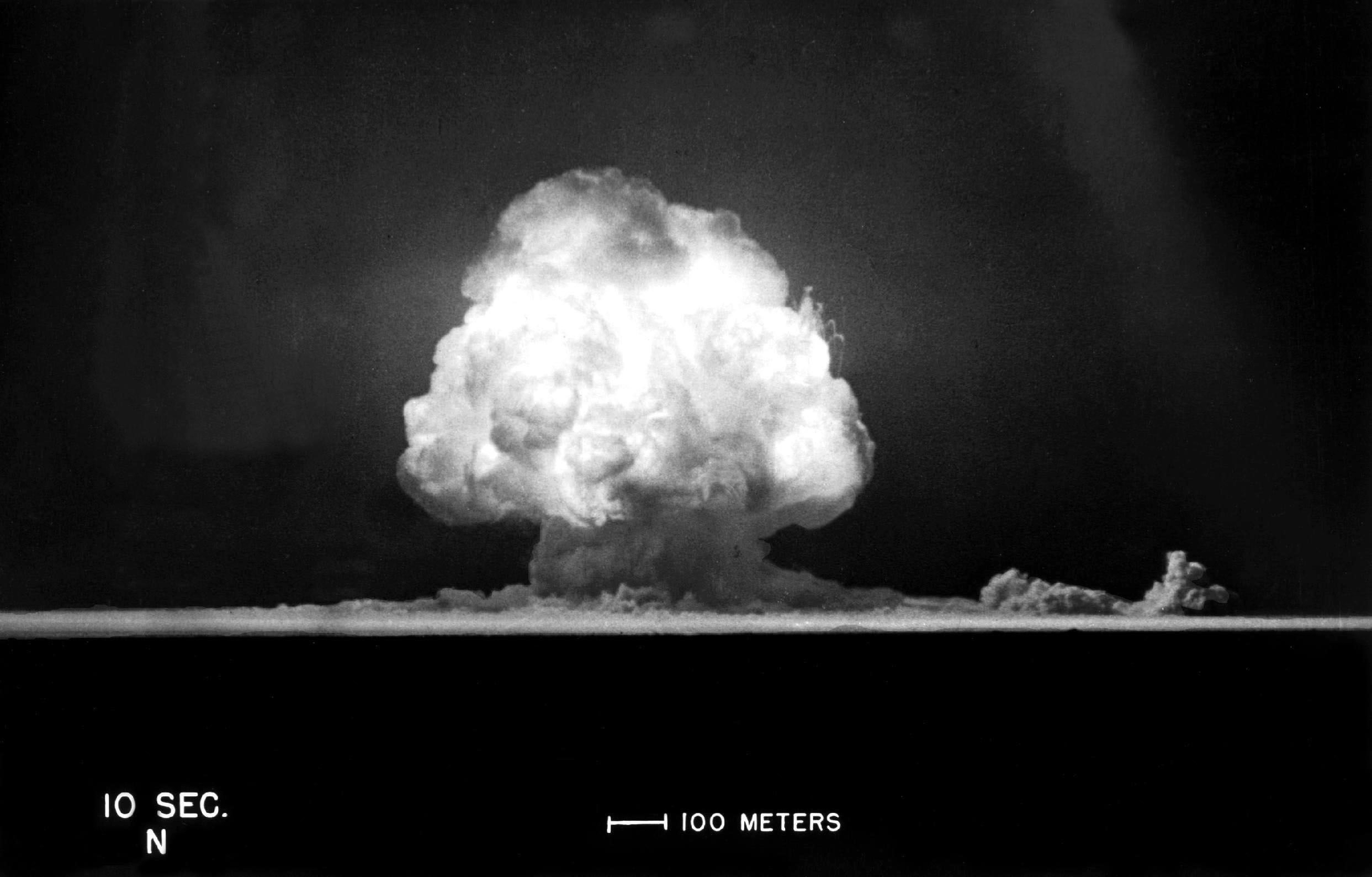

The states of Nevada and Utah were home to nuclear testing from 1951 to 1992, when the U.S. government tested nuclear weapons on a patch of land referred to as the “Nevada Test Siteâ€. The test site is where 928 American and 19 British nuclear tests were conducted, producing the famous images of mushroom clouds. In the face of increasing resistance from environmental groups and native communities, the U.S. government decreased the nuclear tests and shifted the focus towards storing nuclear waste.

In the early 1980’s Congress began considering options for storing the high-level radioactive waste that is produced as spent nuclear fuel is reprocessed into material for nuclear weapons. In response to the growing concerns over nuclear waste storage, Congress passed the federal Nuclear Waste Policy Act in 1982. The Act called on the Department of Energy to choose a location to build and operate an underground nuclear waste disposal facility. The DOE believed the safest way to store this nuclear waste was to bury it deep within the earth.

After studying several sites for the geologic repository, the DOE settled on Yucca Mountain, located less than 100 miles northwest of Las Vegas.

While standing at the base of Yucca Mountain Ian Zabarte explains the importance of this land to the Western Shoshone. Photo: Derrick Broze

Although the project had the support of President George W. Bush, it was opposed by Nevada state officials, environmentalists, and Native activists. Much of the opposition centers around the concern that the mountain will not be able to safely store the waste without contaminating invaluable water supplies and sacred sites. In 2009, environmental and anti-nuclear organizations sent a letter to President Barack Obama calling the selection of the Yucca Mountain site “a purely political decision.†They argued that it has been evident since 1992 that the site “could not meet the EPA’s general radiation protection standard for repositories.â€

Obama opted to end funding for the project, setting off an ongoing legal battle. In August 2013, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ordered the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to approve or reject the DOE application for the proposed waste storage site at Yucca Mountain. While the DOE’s approval process is still stuck in legal limbo, the election of Donald Trump has increased calls for finishing the Yucca Mountain Waste Repository pr

The Fight Against Yucca Mountain Continues

In March 2019, Energy Secretary Rick Perry set aside $116 million to restart licensing hearings on a permanent nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain and to implement interim storage in other states. Perry told the House Appropriations Committee that his budget is designed “to address nuclear waste, enhance national security and reduce future burdens on taxpayers.†Mr. Perry made no mention of the concerns of native communities like the Western Shoshone and the Paiute.

A copy of Native American News from 1992 detailing the fight against the Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Site. Photo: Derrick Broze

Despite Perry’s allocation of funds to restart licensing for the Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Repository, the project is facing extreme opposition from Nevada officials. At a June 13 hearing, Robert Halstead, executive director of the Nevada Agency for Nuclear Projects, testified on behalf of the state in opposition to the Yucca Mountain Waste Site. “Nevada has never been more opposed to Yucca Mountain. Our opposition has never been more bipartisan and has never been stronger,†Halstead told reporters.

Further, Halstead stated that the project “contradicts the foundational principle of geologic disposal†because the site itself “must prevent the radioactive contamination of groundwater in the accessible environment for tens of thousands to a million yearsâ€. Halstead said the Yucca Mountain project does not meet this requirement because it would require the creation and implementation of man-made barriers to prevent contamination of groundwater. According to Halstead the state of Nevada has filed 218 legal challenges to the license application before the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and plans to file 30 more.

Meanwhile, Senator Lisa Murkowski of Alaska is sponsoring a bill that would create a new government agency in charge of handling nuclear waste. The bill also calls for including local consent to become part of the decision-making process. However, the bill does not guarantee residents a veto to stop potentially dangerous nuclear waste sites in their community.

A recent opinion piece published by Alex Berezow, a microbiologist and vice president of scientific affairs at the American Council on Science and Health, suggested that Nevada should pay residents a dividend in exchange for storing the nuclear waste. “The state’s refusal to become the nation’s central repository for nuclear waste means that we are forced to store it at 80 sites across 35 states — an impractical, expensive and less safe solution,†Berezow writes. “It’s time to tempt Nevadans with an outside-the-box approach: Let’s pay them.â€

While Berezow suggests the federal government pay each Nevadan $500 every year, Ian Zabarte says this proposition is a smack in the face of native people. “I think that’s fraud,†Zabarte told Intercontinental Cry. “Right now, the state of Nevada has received payments equal to taxes to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars for its studies and efforts to get a benefit from the process. Nevada takes those dollars and gives them to Nevadans but not native people.â€

Richard Boland, member of the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe and Research & Grants Coordinator at University of Nevada – Las Vegas, believes the politicians and businessmen in support of the Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Site are short-sighted and incapable of understanding the importance of the land to native people. “The people that are interested and see some potential advantages in these projects have a different mindset. I don’t think they have the attachment to the land that we do. If they go and ruin everything here they can just move on to something else. We don’t have that mindset. We are told we were put here for a reason so we don’t think about moving somewhere else.â€

North end of Yucca Flat, where most tests have been conducted.

For Ian Zabarte and other tribal members who oppose the project, the argument against the Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Site comes down to illegitimate claims over the land which has traditionally been used by the Shoshone and Paiute. “When it comes to our property they cannot prove ownership over our land.â€

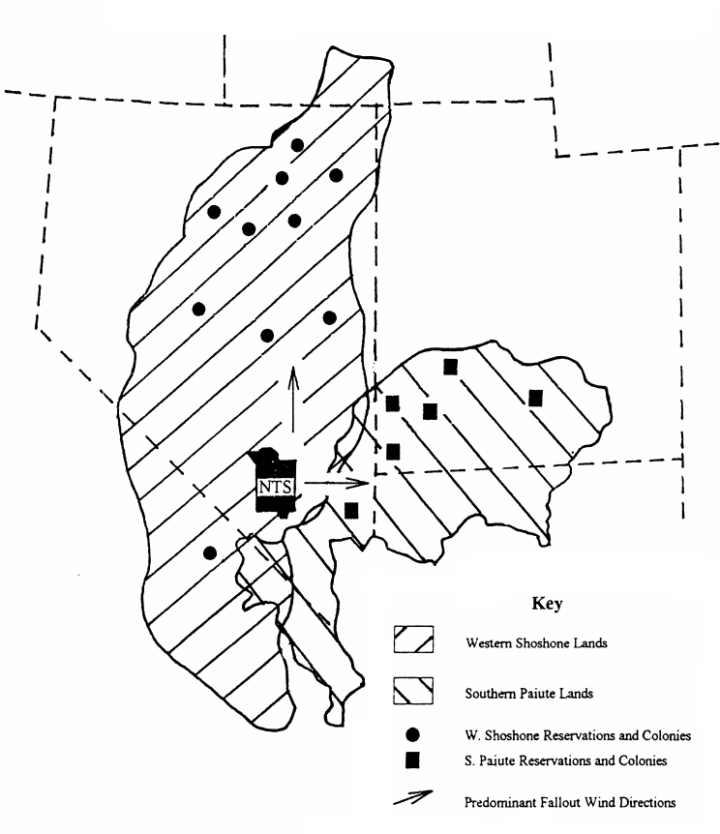

A map showing the traditional lands of the Western Shoshone and Southern Paiutes. The Nevada Test Site is shown in the center; two arrows indicate the most frequent wind directions for nuclear tests. The site of NTS was specifically chosen to limit exposure to major southwestern (upwind) cities.

An Attack on Native Sovereignty

Less than 100 miles from the Nevada Test Site and the planned Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Site reside a number of native nations, including the Western Shoshone, the Moapa Paiute, and the Las Vegas Paiute. The Western Shoshone are one of a dozen Indigenous nations whose chiefs signed the Treaty of Ruby Valley with the governors of the Nevada and Utah territory in 1863. In addition to recognizing the sovereignty of each of the Indigenous nations, the treaty gave the Indian nations ownership over millions of acres of land in Idaho, Nevada, California and Utah. It also allowed settlers access to the land for gold mining and homesteading, but did not give them title.

However, a history of land grabs through controversial legal means saw that land handed over to various agencies of the U.S. government, including the Bureau of Land Management. In 1979, the U.S. put $26 million in a fund for the Shoshone for title to 24 million acres, but the tribe declined the money. The Supreme Court ruled six years later that the settlement, whether officially accepted by the tribe or not, extinguished the Shoshones’ claim to the land.

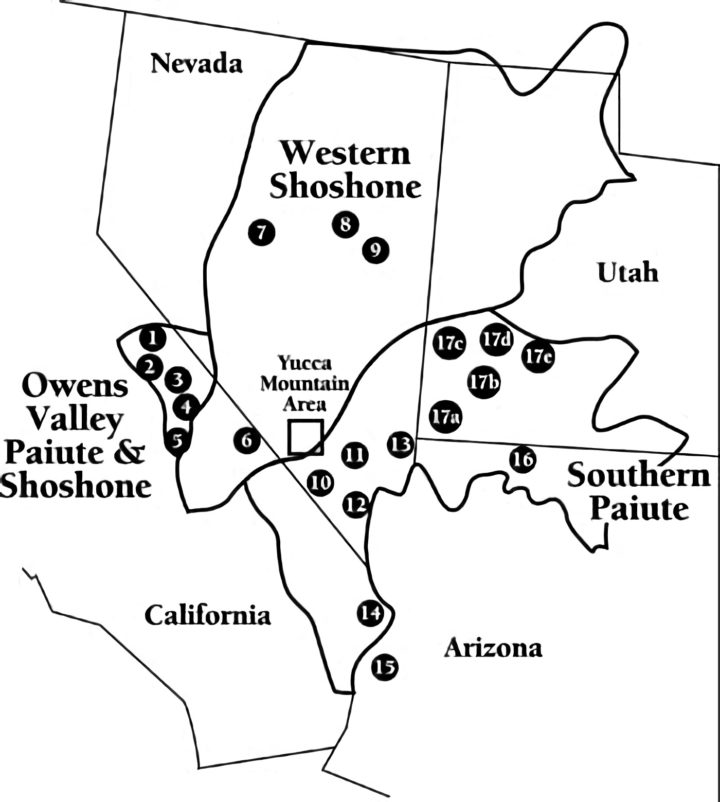

A map showing all federally-recognized Tribes currently located near the Yucca Mountain Site. Source: US Department of Energy

As the U.S. government claimed ownership of traditional Shoshone and Paiute lands, they began using it for testing of nuclear weapons. Richard Boland remembers the testing from his childhood. “When I was little they were still doing testing, so we would feel the tremors. Our elders have always been involved in the fight.†He believes the move from using traditional lands for nuclear testing to storing nuclear waste is another reminder of the constant attack on native peoples way of life.

Trinity Site explosion, 10 seconds after explosion, July 16, 1945.

“We are restricted from accessing that area and as a land-based people you lose a lot in terms of your culture and heritage because our history aren’t contained in books,†Boland stated from behind his desk at the University of Nevada – Las Vegas. “So usually when you go out with your elders and you’re in a certain area, that will prompt them to share whatever stories are related to that area. By us being restricted from that land, not just Yucca mountain, but all the land that has been subsumed by others, you lose a part of your history. In that way it has had a big impact.â€

For Ian Zabarte the fight against Yucca Mountain and theft of native lands is a fight against the ongoing genocide of the native peoples of North America. “We are dealing with two different things. One is genocide, which is a crime against all of humanity, and the process pollutes the planet and changes the planet’s chemistry,†Zabarte says while shuffling through stacks of paperwork related to his 30 year battle against the Yucca Mountain Waste Site. “The other is our agreement with U.S., and we can enforce those treaties but we need to relieve ourselves of the genocide that is ongoing.â€

Although Zarbarte’s claims of genocide may sound extreme in some political circles, the argument for recognizing the ongoing mistreatment of native communities as part of a centuries old genocide is gaining ground. Most recently California Governor Gavin Newsom issued an apology to California Native American Peoples for the “many instances of violence, mistreatment and neglect inflicted upon California Native Americans throughout the state’s historyâ€.

Newsom admitted that California Natives have suffered state sanctioned violence, discrimination, and exploitation. The Governor’s Executive Order acknowledged the 1850 California “Act for the Government and Protection of Indians,†which removed natives from their traditional lands, separating children and adults from their families, languages and culture. The Governor also acknowledged that between 1850 and 1859 the governors of California used private armies and militias against indigenous communities in the state.

“We can never undo the wrongs inflicted on the peoples who have lived on this land that we now call California since time immemorial, but we can work together to build bridges, tell the truth about our past and begin to heal deep wounds,†Newsom stated.

As part of this effort Governor Newsom announced the creation of a Truth and Healing Council to allow California Native Americans to expose the truth about the abuse of their ancestors. Newsom said this is the first time a state has corrected the historical record and acknowledge wrongdoing.

Although Ian Zabarte appreciates the sentiment of California’s Governor, he believes the U.S. government as a whole is still refusing to acknowledge the sovereignty of Indigenous peoples.

“The U.S. government has not dealt with the factual, existing rights of Indian people, of native american, indigeous people. They’ve only dealt with their concept, based on their religion, and it violates the basic human rights of Shoshone people,†Zabarte said. “It’s a crime against humanity. So we are trying to correct those things. We need to stop the genocide – the systematic process used to dismantle our living life ways – we need to correct it, and prevent it from happening in the future.

Derrick Broze writes for IntercontinentalCry, an organization working on behalf of indigenous peoples worldwide.

This article appeared in July at IntercontinentalCry.