By Andrew Cockburn

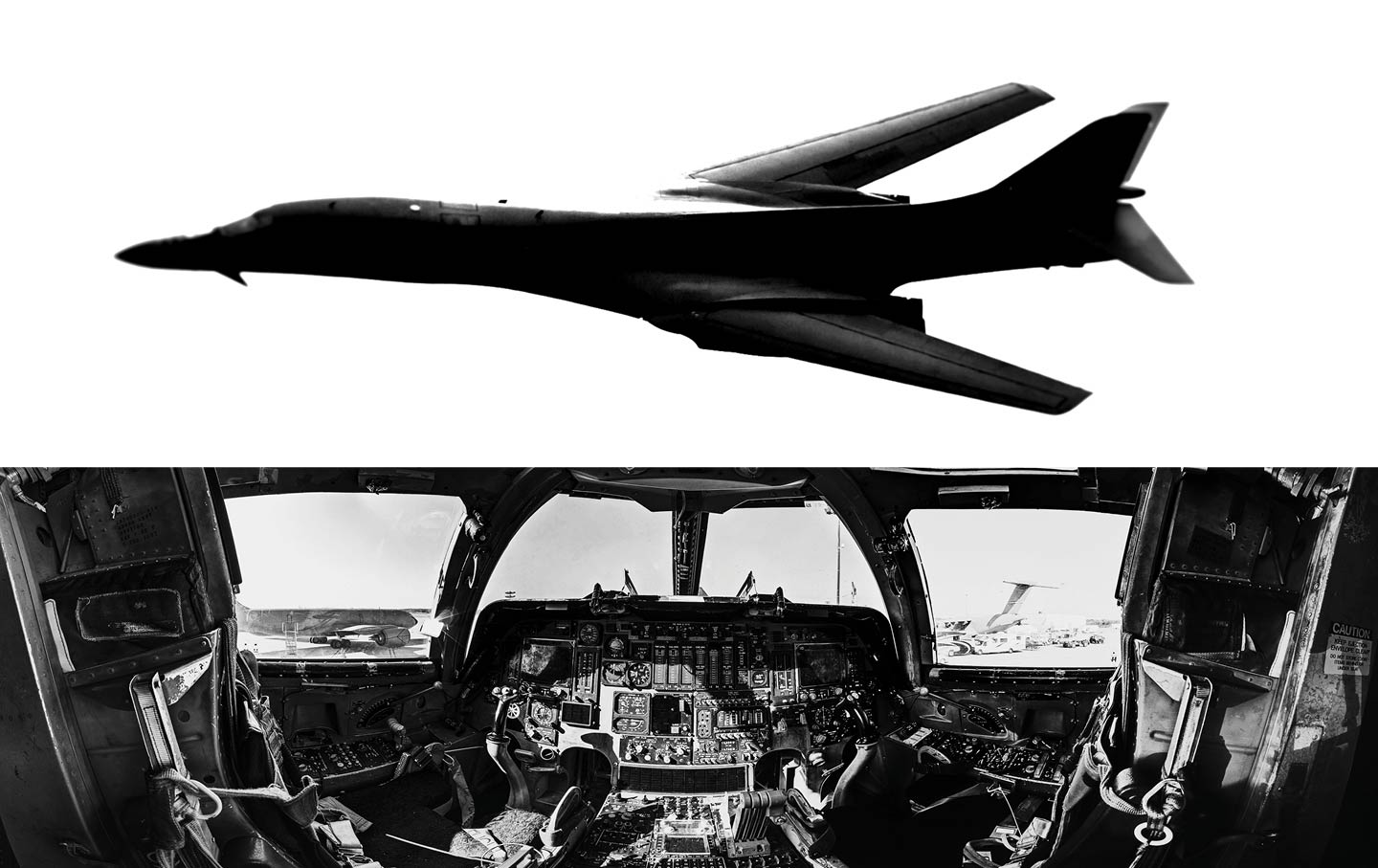

In plane sight: The B-1 bomber is notoriously unreliable. But on the plus side, it’s very expensive.

Innumerable wars originate, wrote Alexander Hamilton in Federalist No. 6, “entirely in private passions; in the attachments, enmities, interests, hopes, and fears of leading individuals in the communities of which they are members.†As an illustration of this truth, he cited the case of Pericles, lauded as one of the greatest statesmen of classical Athens, who “in compliance with the resentment of a prostitute, at the expense of much of the blood and treasure of his countrymen, attacked, vanquished, and destroyed the city of the Samnians†before igniting the disastrous Peloponnesian War in order to extricate himself from political problems back home.

It should come as no surprise that this version of Athenian history is not echoed by orthodox historians, despite credible sources buttressing Hamilton’s pithy account. Instead, Pericles’s attack on Samos is generally ascribed to his concern for protecting a democratic regime in the neighboring city of Miletus or the need to preserve Athenian “credibility†as a great power.

The compulsion to endow states and leaders with respectable motives for their actions is far from confined to ancient historians. It extends across the spectrum of contemporary foreign and defense policy analysis and commentary, from academic ivory towers housing international relations and national security studies departments to think tanks, research institutes, and, of course, media of every variety. Thus, in modern times, two former national security eminences for the Brookings Institution stated that the goal of expanding NATO into Eastern Europe in the 1990s was to “promote peace and stability on the European continent through the integration of the new Central and Eastern European democracies into a wider Euro-Atlantic community, in which the United States would remain deeply engaged.â€

Actually, it wasn’t. The driving force behind the expansion, which ensured Russian paranoia and consequent instability in Eastern Europe, was the necessity of opening new markets for American arms companies, coupled with the prospect of political reward for President Bill Clinton among relevant voting blocs in the Midwest.

Outsiders generally find it hard to grasp an essential truth about the US military machine, which is that war-fighting efficiency has a low priority by comparison with considerations of personal and internal bureaucratic advantage. The Air Force, for example, has long striven to get rid of a plane, the inexpensive A-10 “Warthog,†that works supremely well in protecting ground troops. But such combat effectiveness is irrelevant to the service because its institutional prosperity is based on hugely expensive long-range (and perennially ineffective) bombers that pose lethal dangers to friendly soldiers, not to mention civilians, on the ground. The US armed services are expending vast sums on developing “hypersonic†weapons of proven infeasibility on the spurious grounds that the Russians have established a lead in this field. Despite the fact that hundreds of thousands of veterans of the post–9/11 wars suffer from traumatic brain injury induced by bomb blasts, the Army has insisted on furnishing soldiers with helmets from a favored contractor that enhance the effects of blasts. The Navy’s Seventh Fleet arranged its deployments around Southeast Asia at the behest of a contractor known as “Fat Leonard,†who suborned the relevant commanders with the help of a squad of prostitutes.

Fat Leonard’s inducements were not, of course, limited to carnal delights. The corrupt officers also received quantities of cash (in return for directing flotillas to ports where he held profitable supply contracts), thus confirming the timeless maxim that “follow the money†is the surest means of uncovering the real motivations behind actions and events that might otherwise appear inexplicable. For example, half the US casualties in the first winter of the Korean War were due to frostbite, as I learned from a veteran of the conflict who related how, in the freezing frontline trenches, soldiers and Marines lacked decent cold-weather boots. Like some threadbare guerrilla army, GIs would raid enemy trenches to steal the warm, padded boots provided by the communist high command to their own troops. “I could never figure out why I, a soldier of the richest country on earth, was having to steal boots from soldiers of the poorest country on earth,†my friend recalled in describing these harrowing expeditions. The “richest country on earth†could of course afford appropriate footwear in limitless quantities. Nor was it skimping in overall military spending, which soared following the outbreak of war in 1950. To the casual observer, it might seem obvious that the fighting and spending were directly related. However, although the war served to justify the budget boost, much of the money was diverted far from the Korean Peninsula, principally to build large numbers of B-47 strategic nuclear bombers as well as fighters designed to intercept enemy nuclear bombers, of which the Russians possessed very few and the Chinese and North Koreans none at all.

Money lost at sea: The US spent about $22.5 billion in R&D costs for just three Zumwalt-class ships, according to the US Naval Institute. (US Navy via Sipa USA)

The reason for this disparity in the allocation of resources should be obvious: The aerospace industry, as aircraft manufacturers had sleekly renamed themselves, was more powerful and demanding than the bootmakers, and so that was where the money went. The pattern was repeated half a century later as American families went into debt to buy armored vests, socks, boots, and night-vision goggles for sons and daughters in Iraq, even as some $50 billion was poured into esoteric devices to detect insurgents’ homemade $25 bombs. One such was Compass Call, a $100 million Lockheed EC-130H aircraft equipped with ground-penetrating radar that could supposedly seek out buried explosives. Unfortunately, a military intelligence unit in Baghdad in April 2007 concluded, after analyzing hundreds of flights, that the system had “no detectable effect.â€

Raids on the public purse such as these are rendered easier by a widening gulf between the military services and the population at large. For decades, thanks to the draft, most Americans had either served in the military or knew someone who had, and so were aware at some level that the services were beset with bumbling bureaucratic incompetence. But these days most people are ignorant of the military world and rely for insight on a press that is all too often either clueless or compromised by the need to maintain access to self-interested sources. This lack of awareness is exacerbated by an aversion to challenging military claims regarding technology, not least because such claims are broadcast and vigorously promoted by a well-endowed public relations apparatus. The June 2014 disaster in which a B-1 bomber, thanks to endemic technological shortcomings, killed six friendly servicemen (five Americans and one Afghan) provided an instructive example. The Air Force responded rapidly to the tragedy by inviting a New York Times reporter for a joyride on a B-1, thereby generating a predictably uninformed but positive review of the lethal (especially to friendly troops and civilians) machine.

Even when a weapons program’s deficiencies are too egregious to be ignored, media criticism seldom strays beyond timidity, such as decrying excessive “waste†in the program, without probing how and why huge costs have become routine. The truth that ballooning costs can be directly ascribed to ever more complex technology, as was exposed in detail as far back as the 1980s by the Pentagon analyst Franklin “Chuck†Spinney, is never addressed. Thus, for example, the alarm prompted by Russia’s takeover of Ukraine in 2014 generated budgetary rewards for the Pentagon but relatively puny forces in terms of fighting strength—initially a mere 700 troops in Poland, for example, to face the putative Russian hordes poised to invade. Overall, despite remorseless growth in spending, the US military continues to shrink, fielding fewer ships, aircraft, and ground combat units with every passing decade. Remarkably, more money apparently produces less defense.

Uninterested in such prosaic realities, liberals bemoan the money spent on arms and lament the “militarism†manifest in America’s appetite for war, while avoiding the underlying driving force: the military services’ eagerness for ever more money, shared with the corporations that feed off them, as well as the officers who will cash in with high-paid employment with these same corporations once they retire. In other words, the military is not generally interested in war, save as a means to budget enhancement. Thus, when President Donald Trump was induced to order a minor surge in Afghanistan in 2018, a conclave of senior Marine generals agreed to go along with the plan on the grounds, according to someone who was present at the relevant meeting, “that it won’t make any difference in the war, but it will do us good at budget time.†Col. John Boyd, the former Air Force fighter pilot who famously conceived and expounded a comprehensive theory of human conflict, once pointed out that there was no contradiction between the military’s professed mission and its seeming indifference to operational proficiency. “People say the Pentagon does not have a strategy,†he said. “They are wrong. The Pentagon does have a strategy. It is: ‘Don’t interrupt the money flow, add to it.’â€

Once this salient truth regarding our military strategy is understood, it becomes simpler to make sense of US actions, notably in provoking a new Cold War with Russia as well as toadying to the repellent Saudi regime—an ever eager customer for US arms—even in the face of its complicity in the 9/11 attacks or its war crimes in Yemen.

The true dynamics driving actions such as those described above are usually well understood internally, even if they are unnoticed or misunderstood by outsiders. Civilians may not comprehend what is at stake in the interservice battle for budget share, but every officer in the Pentagon surely does. Likewise, frontline soldiers and Marines are well aware that they are condemned to rely for support on the inaccurate B-1 bomber because the Air Force is determined to protect its lucrative bomber mission at the expense of the effective A-10.

While people have no problem in understanding the real political dynamics affecting their own group, there appears to be a barrier to understanding that the same dynamics might apply elsewhere. For example, Marines in Afghanistan’s Helmand Province long cherished the support of the powerful tribal leader Sher Mohammed Akhundzada in battling the Taliban, whose forces he would helpfully identify. But the enemies he designated were all too often not Taliban but supporters of his chief business rival in the drug trade, another tribal leader who was meanwhile enjoying a similarly fruitful alliance with the British forces sharing the same headquarters as the Marine Corps. Overall, this woeful ignorance pervaded the entire US-led misadventure in Afghanistan, a saga of disastrous errors that is comprehensible only if it is assumed that the goal of the effort was “to do us good at budget time,†which, as the trillion-dollar-plus tab for the war attests, it certainly did.

Comprehending that it is private passions and interests that customarily propel acts of state makes the consequences for their victims appear even more disgusting. The CIA long ago struck budgetary gold in covert warfare, leading it to ultimately forge a profitable partnership with Al Qaeda in its various assorted nominations. The agency’s involvement in the Syrian civil war, in de facto alliance with Al Qaeda spin-offs, is commonly cited as the most expensive in its history. Equally gruesome, sanctions on Iraq throughout the 1990s, which killed hundreds of thousands of children, were supposedly enforced to compel Saddam Hussein to abandon his purported arsenal of weapons of mass destruction. But, as was later confirmed to me by the chief UN weapons inspector for much of the period, Rolf Ekéus, the Clinton administration knew very well, at least from the spring of 1997, that Hussein had no WMD, because he, Ekéus, had secretly told them so and planned a conclusive report to the UN detailing his findings. There would therefore have been no legal basis for continuing the embargo. But Clinton was fearful that lifting sanctions would cost him politically, since the Republicans would surely trumpet complaints that he had “let Saddam off the hook.†Secretary of State Madeleine Albright therefore announced that sanctions would continue, WMD or no, with the predictable and intended result that Hussein ceased cooperation with the UN inspectors and uncountable more Iraqi children died.

Sometimes the naked pursuit of self-interest is unabashed, but even when the real object of the exercise is camouflaged as “foreign policy†or “strategy,†no observer should ever lose sight of the most important question: Cui bono? Who benefits?

Andrew Cockburn is the author, with Patrick Cockburn, of Out of the Ashes: The Resurrection of Saddam Hussein. His most recent book is Kill Chain: The Rise of the High-Tech Assassins.

This article was published on September 9 at The Nation.