By Nick Engelfried

A student-led effort to get fossil fuel money out of university research is building on the divestment movement’s biggest successes.

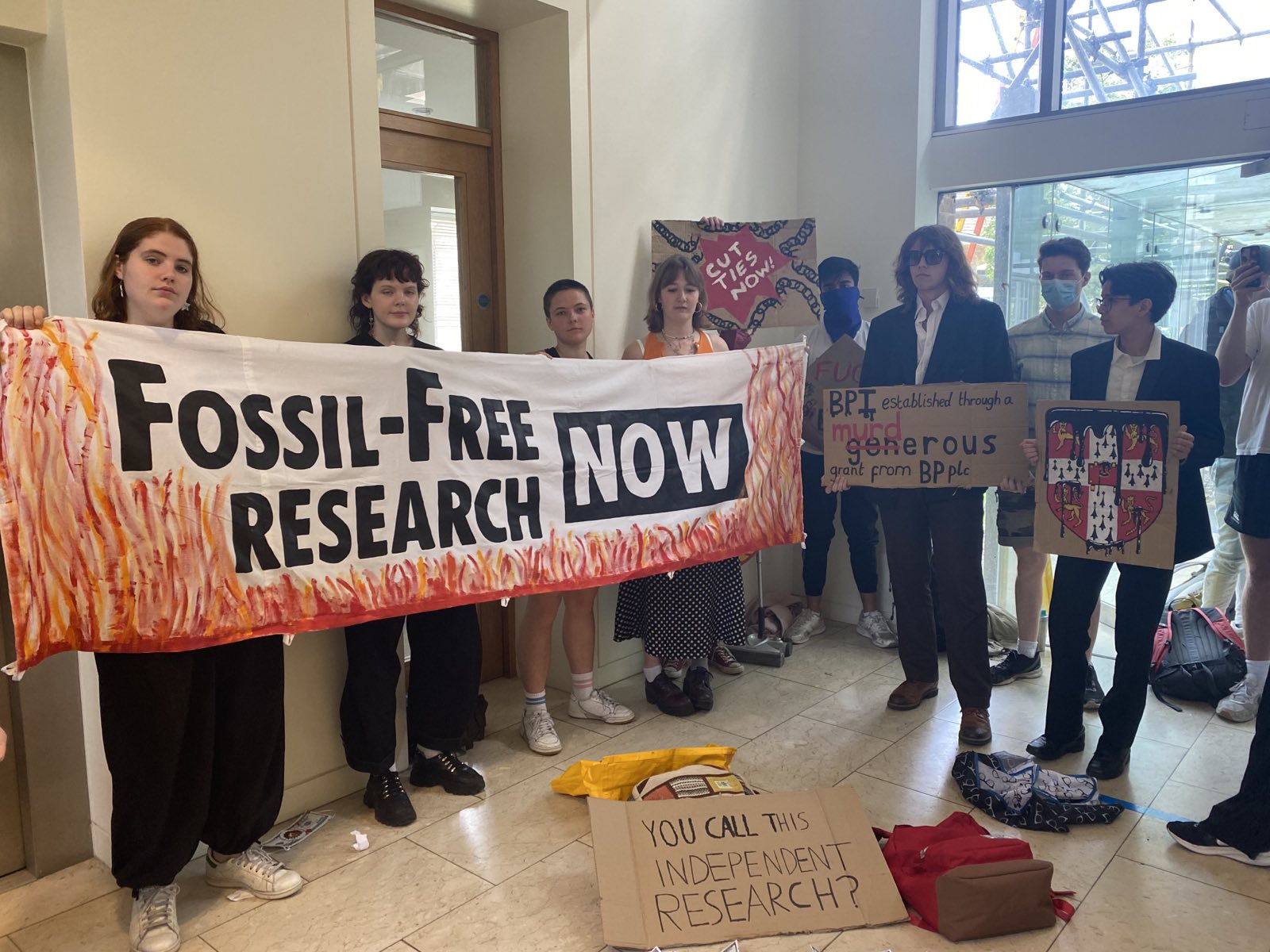

When over 40 Cambridge students and academics occupied the elite U.K. university’s BP Institute earlier this year, they were escalating one of the newest, fastest-growing campaigns focused on dissociating higher education institutions from fossil fuels. For just over an hour, activists from the grassroots initiative Fossil Free Research held a sit-in inside the building named after one of Europe’s largest oil producers, while making speeches and staging a street theater production that called attention to links between BP and the school.

“We’re drawing attention to how the fossil fuel industry continues to infiltrate prestigious academic institutions, mooch off their credibility, and even exert influence over the production of knowledge crucial to shaping climate policy,” said Ilana Cohen, a lead organizer for the international Fossil Free Research campaign, who is currently a senior at Harvard.

Fossil Free Research launched earlier this year and aims to build on momentum from the successful fossil fuel divestment movement at universities in the U.S., U.K. and beyond. It is pushing higher education institutions to commit to not taking money from coal, oil and gas corporations for research, particularly that relates to climate science. “These companies shouldn’t be shaping research when they have a clear incentive to distort it,” Cohen said.

As it has spread to colleges and universities across the United States and Europe, Fossil Free Research has effectively utilized existing communication channels and networks developed by the campus-based divestment movement. It all started when students on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean began talking about how to continue momentum from some of the biggest divestment wins so far.

Building on divestment momentum

Last October, Cohen and other Harvard students were celebrating a victory years in the making. After almost a decade of student campaigning, the Ivy League school announced it would allow fossil fuel investments in its $42 billion endowment to expire — effectively divesting from the industry.

Even mere months earlier, this development would have seemed nearly impossible. The school’s administration had repeatedly refused to divest in response to calls for action from students. But the Divest Harvard campaign, of which Cohen was a leader, continued to escalate, drawing support from Harvard faculty and alumni. In one of the campaign’s most iconic moments, students from Harvard and Yale stormed the field during a football game between the two schools, unfurling pro-divestment banners as 30,000 surprised football fans looked on. This and other high-profile actions put pressure on the administration, eventually leading to Harvard’s October 2021 divestment announcement.

In fact, last year saw a wave of victories for the campus-based divestment movement — not just at Harvard, but at higher education institutions across the U.S. including Columbia, Tufts, Rutgers, University of Southern California, University of Michigan and Princeton. In 2020, Cambridge, one of the United Kingdom’s most exclusive schools, had also announced it would divest. All of this progress left students like Cohen wondering what came next for their movement.

“Soon after Harvard’s divestment announcement, our campaign went on a strategy retreat to decide on our next steps,” Cohen said. “Winning on divestment was huge. But our movement’s theory of change goes beyond that. Our goal is to stigmatize the fossil fuel industry to the point where its political power is diminished so we can finally see renewable energy deployed on a massive scale.”

Cohen and other Divest Harvard organizers were in touch with students at other schools who had also recently won divestment campaigns and found themselves trying to chart a path forward. When Cohen did a semester abroad at Cambridge that spring, she was able to further strengthen ties and communication between Harvard and the U.K. school, where students were looking into the influence fossil fuel companies exert through entities like the BP Institute.

Meanwhile, students at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., were investigating the money behind their school’s Regulatory Studies Center, or RSC. A report released by Public Citizen accused the RSC of promoting anti-regulation views that often seemed to have little grounding in data but matched the ideology of donors like the Koch Foundation. Like Cambridge, George Washington had committed to divest its endowment from fossil fuels in 2020. But now, concern that companies like the oil-rich Koch Industries were shaping the school’s research priorities led students to scrutinize this additional link to the industry.

“It’s hugely problematic to have an institute at our university accepting money from actors like Koch,” said George Washington senior Jake Lowe, who was inspired to get involved in this new effort after seeing the divestment campaign win. “The divestment victory made me realize students have real power to make an impact on these kinds of issues at our university.”

In early 2021, Lowe did a fellowship with Sunrise Movement focused on uncovering and shining a light on corporate influence at the RSC. This led to him and other George Washington students having conversations with organizers at Cambridge and Harvard about a coordinated effort to get fossil fuel research money off college campuses.

“We quickly realized we were onto something that was even bigger than our three universities,” Lowe said. Soon, the students were drawing up plans for a true international campaign.

Getting fossil fuels out of research

The reality is that while university endowments are important, they represent only one of the ties the academic world has to the industries most responsible for causing the climate crisis. At many colleges and universities, fossil fuel companies help pay for construction of new buildings, donate to academic programs and even fund climate research through entities like the BP Institute — whose projects have included work on carbon sequestration technology. A 22 million pound donation from BP (equivalent to more than $30 million at the time) helped establish the institute in the early 2000s, and the center has borne the oil giant’s name ever since.

In March, Fossil Free Research released a letter signed by almost 500 U.S. and U.K. academics calling on higher education institutions to refuse fossil fuel money for climate research, with signatories including renowned climate researcher Michael Mann, NASA scientist Peter Kalmus, and philosopher and social justice advocate Cornel West. The letter now has over 730 signers from more than 130 educational institutions. The document was meant to show that prominent figures in the academic community support the goals of Fossil Free Research — but it had a much larger impact than even the campaign’s organizers had predicted.

“Releasing the letter was the moment we really went public with our campaign, and it kickstarted movement momentum to a degree that we honestly couldn’t have foreseen,” Cohen said. “Students were really excited to get involved.” Soon decentralized Fossil Free Research organizing hubs were taking root at colleges all over the U.S. and U.K., many of them schools where students had already won divestment victories.

At this point, Fossil Free Research was still a campaign in its infancy without an official board, the ability to accept tax-deductible donations or other organizational infrastructure available to more established nonprofits. Even so, the movement started growing at a speed that quickly outpaced efforts to set up a more formalized organization.

“Because our leaders were involved in previous divestment organizing, we were already connected to a network of students across the country who became interested in this new campaign,” Cohen said. By using the divestment movement’s email lists, social media platforms and Slack channels, Fossil Free Research leaders spread their campaign much faster than would otherwise have been possible.

The sit-in inside the BP Institute at Cambridge last spring was one of the new movement’s most confrontational actions yet, and coincided with solidarity events at Oxford and George Washington. All of this organizing has already had an effect. In July, Cambridge announced it would rename the BP Institute — a blow to the public image of the largest U.K.-based oil giant. Even more significantly, faculty at the school will hold a binding vote this fall on a proposal to ban research money from companies involved in building new fossil fuel infrastructure, exploring for fossil fuel reserves or lobbying against climate action.

At George Washington, according to Lowe, the Women’s, Gender and Sexualities Studies Department has become the first university department to take a pledge to ban donations from the fossil fuel industry — and student activists hope the School of Public Health will vote on a similar policy soon.

“That would be a really big deal,” Lowe said. “As other departments and schools within GW show their support for fossil free research, pressure will build for institutes who are deeply connected to the fossil fuel industry, like the RSC, to act.”

Growing a movement

When students on a handful of U.S. college campuses launched the country’s first fossil fuel divestment campaigns over a decade ago, it took years for their efforts to grow into a true mass movement. This made sense; after all, early divestment leaders had to build a network of communication channels that served as hubs for organizing almost from the ground up. National organizations like 350, Divest Ed and the now-disbanded Divestment Student Network supported this effort by providing training, paid organizing fellowships and other resources.

Fossil Free Research began with almost none of these advantages. However, relying on the divestment movement’s existing communications infrastructure — as well as support from organizations like Sunrise Movement, whose missions overlap with that of the new movement — has allowed it to spread with astonishing speed. This illustrates something important about how climate campaigns led by members of Generation Z grow in the age of Slack, Zoom and social media. It also shows how initiatives like divestment advance the larger climate movement’s goals — not just by winning their own campaigns in the short term, but by laying a strong foundation for future organizing.

This fall, Fossil Free Research is focusing on continuing to grow the movement by recruiting new schools, while also setting up the organizational infrastructure it has so far lacked. “Our goal is to have a staff composed mostly of recent college graduates or other young people,” Lowe said. “And a board with students from different schools giving input in a way that aligns with our values of democratic participation.”

With such a base of support, Fossil Free Research leaders hope other schools will soon see the kinds of successes campaigns at Cambridge and George Washington have begun to experience. “Fossil fuel divestment at universities should mean complete, true divestment from all aspects of the industry,” Cohen said. “That means separating yourself entirely from the companies driving climate breakdown and not allowing them to have a role in research that’s critical to our future. Students overwhelmingly support this. Now it’s up to institutions to understand and recognize that.”

Nick Engelfried is an environmental writer, educator, and activist living in the Pacific Northwest. He is currently working on a book about the youth climate movement.

This article was published on October 3, 2022, at WagingNonviolence.