Nearly 80 years after the first atomic test in New Mexico, a consortium of “downwinders” are documenting the bomb’s impact on their community and organizing for restitution.

By Alessandra Bergamin

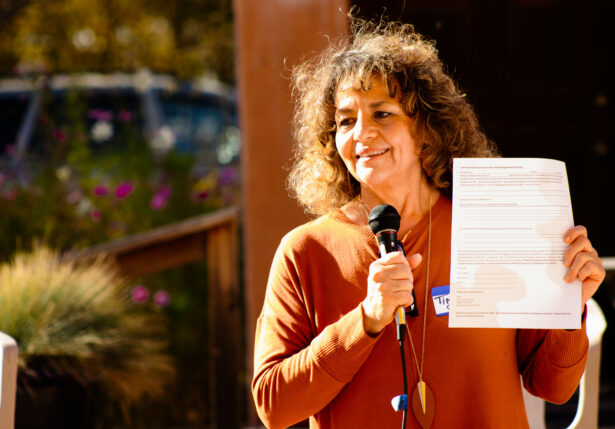

Eighteen years ago, as Tina Cordova read her local newspaper in the town of Tularosa, New Mexico, she noticed a letter to the editor that made her pause. It was written by the now late Fred Tyler, a fellow New Mexican, about his mother’s recent passing from cancer, after having suffered from several types over the course of her life. “I’m wondering,” Cordova recalled Tyler writing, “when we are going to hold our government accountable for the damage they did by detonating an atomic bomb in our backyard?”

In south-central New Mexico, the world’s first atomic bomb was detonated on July 16, 1945. At the time, no information about the test — code-named Trinity by the bomb’s so-called “father” J. Robert Oppenheimer — was shared with the public, including the more than 13,000 New Mexicans living within a 50-mile radius. Less than a month later, two atomic bombs were used to decimate the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was only after the bombings on Japan that the explosion of light and sound in New Mexico that day was revealed to be the origins of nuclear warfare. Nearly 80 years later, those closest to the Trinity site are still fighting for justice.

After Cordova read Tyler’s letter to the editor, she contacted him, explaining her personal experience and background in biology and chemistry. Soon, the pair founded the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium or, TBDC. The organization seeks justice and recognition for those impacted by the nuclear weapon cycle in New Mexico, including uranium miners, a large portion of the Navajo Nation and Laguna-Acoma pueblos, and those who have been overexposed to radiation from the Trinity site.

This week, as the world commemorates the 78th anniversaries of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, I spoke with Cordova about documenting history as a form of activism, lobbying for policy changes and the impact of Christopher Nolan’s new film, “Oppenheimer,” on TBDC’s organizing.

You were born and raised in the small town of Tularosa, New Mexico, just over an hour drive from the Trinity site. How have you and those you know been impacted by the Trinity test and the effects of radiation exposure?

In my family, I’m the fourth generation to have cancer. By the time I co-founded the TBDC, I had been diagnosed with thyroid cancer. The very questions I was asked were, “when were you exposed to radiation? Did you ever work with radioactive isotopes? Have you ever worked in a lab facility? Did you ever have a lot of X- rays? Did you work in an X-ray facility?” I said, “no, no, no.” But I was literally raised in a community 45 miles away, as the crow flies, from the Trinity site and was also downwind of the Nevada Test Site. Before that, for many, many years, I had seen people dying around me from the most obscure cancers. I had a first cousin, we were raised like brother and sister, and he had a brain tumor so rare, they told us there were probably only a handful of people in the world with that kind of cancer.

I’ll also share a conversation I had recently with a friend I grew up with, who lives on the Mescalero Apache reservation. He said, “I just wanted to let you know that my sister has been given a few months to live.” I used to babysit for her husband when I was in high school, and I was devastated to receive that news. Then my friend said his ex-wife, who I was also raised with and who was part of my circle of friends growing up, has stage four cancer. Finally, he added, “Tina, I don’t know if you know this yet, but my nine-month-old grandson is receiving care at a hospital in Houston for a blood disorder and is having chemotherapy. My family has been hit really hard as of late.” I was just blown away by that.

I wish I could say that my family and my friend’s family are unique, but they are not. We document this level of cancer over and over in a multitude of families in New Mexico. It’s not a rare occurrence.

The Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium has been working across the West for 18 years now. Could you describe the kind of organizing and actions the TBDC engages in?

We do outreach work in communities where we hold town hall meetings and conduct health surveys that document people’s histories — and their family’s histories — of cancer, sickness and illness. We have been doing this for about 15 years and have probably collected around 1,000 surveys. The surveys come in nearly every day, especially as we’re receiving a lot of attention. Right now, we’re planning to do outreach in a small community called San Patricio at the request of the people who live there. They asked us to hold a town hall meeting and potentially find some volunteers to collect health surveys.

We have always believed that these histories would be important to our campaign for justice. You will not see this history in other places — so we really do believe it’s up to us to document and preserve it. Similarly, we recently got a grant to work with local educators to develop a curriculum so that this history is taught as part of New Mexico’s history, U.S. history and international history, because it is all three of those things.

Then, there’s our active lobbying work. Alongside a national coalition of frontline community members and other organizations, we lobby for the passage of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, or RECA amendments. When we go into communities, we pass out printed literature that advises people on what they can do to assist us in getting those amendments passed.

We also hold three annual events. We go to the Trinity test site twice a year when they open it to thousands of visitors. We hold a peaceful demonstration to educate people about the issue and to make sure they understand the counter-narrative. We also hold an annual candlelight vigil in July on the Saturday closest to the anniversary of the Trinity test. We light luminarias — round paper bags with sand and a votive candle — in memory of people who have lost their lives to cancer. We light about 800 and call out the names of loved ones who have passed. It’s a way for us to memorialize that we were, and still are, negatively affected by the bomb.

How has the public reacted to TBDC’s demonstrations outside the Trinity site?

When we first started going, we would receive mostly negative reactions from people — people yelling at us, cussing at us, throwing us the finger, those kinds of things. But now there’s a lot more awareness, and we’re getting many more people giving us a thumbs up, or honking, or rolling down the window and saying, “Don’t stop, keep up the fight!” There’s just been a lot more people stopping to engage with us in a positive way and asking how they can help.

Earlier you mentioned the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act or, RECA, and TBDC’s lobbying work around the issue. Could you explain what RECA is and why it’s important for downwinders and former uranium miners in New Mexico and elsewhere?

RECA is a program established in 1990 that gives compensation to uranium miners who mined before 1971 and people who lived downwind of the Nevada Test Site in a few counties in Arizona, Nevada and Utah. We’ve been fighting for the expansion of RECA, so that it not only covers the post ‘71 uranium workers but all the other states that were left out — including, and most noticeably, New Mexico, where the first atomic bomb was detonated.

Right now, the cut off for RECA for downwinders is right at the New Mexico-Arizona border. But I always say there was no lead curtain that offered anybody protection in New Mexico — it didn’t work that way. So we’re fighting to include all of the state of New Mexico, as well as Colorado, Idaho, Montana and Guam [which was impacted by nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands some 1,200 miles west], and then full coverage for the states of Arizona, Utah and Nevada.

We have also asked that they increase the one time payment of restitution to $150,000 to keep up with today’s cost of living. Then we have asked for medical coverage for downwinders who qualify — since a lot of people in the American West live in rural areas where there is no medical care and travel is required. When my dad got so sick that there was nothing else they could do for him in New Mexico, we took him to Houston, Texas, which is not an unusual occurrence. We’d also like to establish radiation exposure screening and education clinics where people can go annually and be screened for cancer so their illness is caught early and their prognosis is improved.

Over the years how have you approached lobbying for RECA amendments and what has changed, if anything?

When we first founded the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium, Fred Tyler and I were so naive. We truly believed that once we brought this to the attention of our government they would immediately take care of us. At the point of starting the organization, we didn’t know about RECA, and when we found out they were taking care of other downwinders, you can imagine the shock and betrayal we felt that nothing had ever been extended to us. So we didn’t really start lobbying for RECA amendments until about three years after we started the organization. At that point, even our own senators and representatives in New Mexico were reluctant to embrace the idea that we had been harmed somehow, and it took a lot of work to get them to realize that. When we testified in Congress — I testified for the first time in 2018 — we thought we had developed momentum. Then we testified in the Senate Judiciary Committee, but we hadn’t seen a vote brought to the floor of the House or the Senate.

Then, last week, a historic event took place: The U.S. Senate passed the amendments to RECA as part of an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act. Exposure to radiation is not discerning — it affects the young, the old, the Black, the white, the male, the female, the Democrat and the Republican alike. If you take a look at the profile of the states that we’re trying to add to RECA, most of them are red states, yet it’s Republicans who have been telling us for a very long time that this is untenable because it’s going to cost too much. We’re excited for this show of bipartisanship, and we hope the House of Representatives will view this the same way. They can either become part of a winning process and pass the RECA amendments or they can become part of those who will go down in history as blocking justice for the people of the American West. It’s just that simple.

“Oppenheimer” was released in late July, resurfacing conversations about the creation of the atomic bomb and the nuclear weapons industry. What was your reaction to the film and what is the position of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium?

When I saw the film I immediately recognized that not a single person from New Mexico was portrayed in the film. They didn’t show somebody pumping gas, they didn’t show somebody serving a meal, they didn’t show somebody cleaning a house — nothing. And certainly, they didn’t show us living adjacent to the Trinity site. It was as if the Manhattan Project and the Trinity test took place in a complete vacuum.

In the movie, they show the Pajarito Plateau, where Los Alamos was built, and they show these beautiful landscapes and there’s nothing there. It’s just a vast, empty, beautiful landscape. But we know none of that’s true. The Pajarito Plateau was completely filled with active farms and ranches and those people had their land stolen by the U.S. government to establish Los Alamos. Even around the Trinity site, there were men tending cattle who had their hair and their beards turned white afterwards. The cows had their skin burned off of them.

Why didn’t the film reflect on any part of that so that people could really understand that although you may survive — and we did survive Trinity — for so many, it was the beginning of the end. If you’re trying to get people to understand that nuclear weapons aren’t the answer, how about embracing that?

Do you think the film’s release will help or hinder the work of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium?

I think the only thing that can happen is that it will help us. But, I will say, the film could have helped us a lot more. Before the film’s release, we did a lot of outreach to ask the filmmakers to include a simple panel at the end of the film that would have acknowledged our sacrifice and our suffering, but we never heard back. We have received more attention because they left us out, but if they had included us, it would have been even more helpful. Tens of millions of people who see this movie would have seen that panel and might have engaged with us. So it’s disappointing, and it shows complete and total arrogance. It’s also exploitation.

Could you describe some of the successes the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium has had over the years?

This work has been a series of ups and downs, and it seems like we take a step forward and then a couple of steps back. It’s positive when our lobbying results in a new co-sponsor to a bill in the House or the Senate, or when we’ve met with key members of Congress and they’ve promised us a hearing and we get that hearing. Those things we appreciate. Those are all positive outcomes. But when we can’t reach Congress sufficiently to produce the end result we’re after — that’s a step back. We only know one way though, and that’s moving forward. We can’t stop what we’ve started. We have promised everyone that we will keep this work going, and we will.

Are there any upcoming actions or events for the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium?

We’ll be at the Trinity site for the visitor day in October, doing what we’ve always done. Because of “Oppenheimer” we’ll probably have more people standing with us in peaceful protest and that will give us an opportunity to engage with more people. If, by chance, the RECA amendments have passed, it will be a celebration more than anything else. We’re holding out hope for that, but it’s hard.

Alessandra Bergamin is a freelance investigative journalist based in Los Angeles. Her work focuses on the intersection of environmental conflict and human rights around the world. She has written for The Baffler, In These Times, Harper’s Magazine, National Geographic, TheNewYorker.com, The Lily, and DAME Magazine among others. She is currently reporting on the overlap of military violence and environmental activism for The Leonard C. Goodman Institute for Investigative Reporting.

This article was published on August 8, 2023 at wagingnonviolence.