Democrats finally have 3-2 majority needed to regulate ISPs as common carriers.

By Jon Brodkin

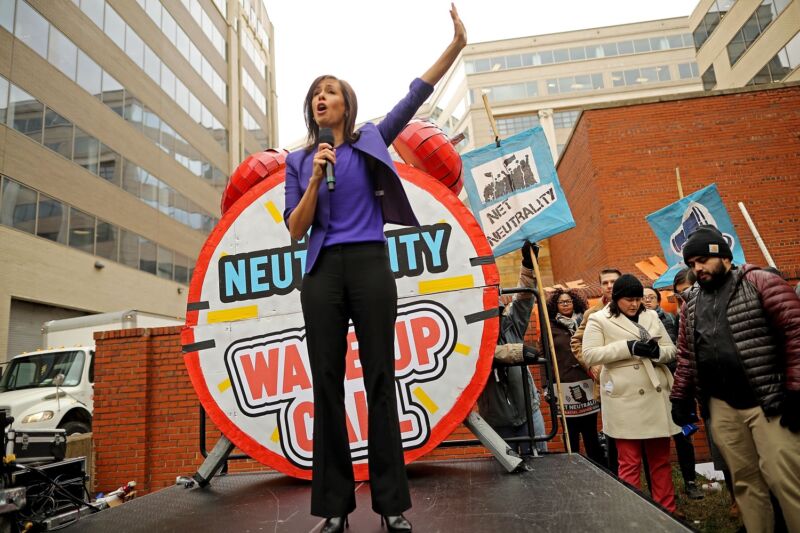

Federal Communications Commission Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel today announced plans to restore net neutrality rules similar to those that were adopted during the Obama era and then repealed by the FCC when Donald Trump was president.

Rosenworcel announced her plans in a speech today, one day after the FCC gained a 3-2 Democratic majority with the swearing-in of Commissioner Anna Gomez. The FCC previously operated with a 2-2 partisan deadlock because the US Senate never voted on whether to confirm President Biden’s first nominee, Gigi Sohn.

“This afternoon, I’m sharing with my colleagues a rulemaking that proposes to reinstate net neutrality,” Rosenworcel said.

The net neutrality rules would prohibit Internet service providers from blocking or throttling lawful Internet traffic and from selling “fast lanes” that prioritize some traffic over others in exchange for payment. Similar to the previous rules, FCC officials said they don’t plan to impose rate regulation or “unbundling” requirements that would force broadband providers to share networks with other companies.

In a fact sheet, the FCC said the proposal would “establish basic rules for Internet Service Providers that prevent them from blocking legal content, throttling your speeds, and creating fast lanes that favor those who can pay for access.”

Vote next month

The first step for the FCC is to vote on a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) that will seek public comment on the rules. The vote on the NPRM is scheduled for October 19. Based on past practice, it will take at least a few months to gather public comments, analyze them, and then propose and adopt final rules.

“We will need to develop an updated record to identify the best way to restore these policies and have a uniform, national open Internet standard,” Rosenworcel said.

Rosenworcel, a commissioner since 2012, criticized the Trump-era FCC’s decision to stop regulating broadband as a common carrier service. She pointed out that the rules were upheld in court and popular with the public, and that the repeal was met with an overwhelming public backlash.

“As a result of the previous FCC’s decision to abdicate authority, the agency charged with overseeing communications has limited ability to oversee these indispensable networks and make sure that for every consumer, their access is fast, open, and fair,” she said.

Just like the Obama-era rules

Rosenworcel’s proposed rules will mostly mirror those approved under then-Chairman Tom Wheeler in 2015, senior FCC officials said in a call with reporters today. The proposal would classify broadband providers as common carriers under Title II of the Communications Act, providing the legal authority to impose net neutrality rules and other regulations.

Broadband providers are likely to argue that rules aren’t necessary because they’ve behaved themselves in the five years since the previous net neutrality order was repealed in 2018. To counter that argument, FCC officials today pointed out that ISPs are required to follow net neutrality rules in individual states even though the federal government doesn’t have uniform rules for the whole country.

Then-Chairman Ajit Pai’s attempt to preempt all state net neutrality rules was rejected in court. California enforces net neutrality rules that mirror what the FCC adopted in 2015 and beat industry attempts to get the state law overturned.

FCC officials said today that nearly a dozen states enforce net neutrality through state laws, government contracting policies, or executive orders. While they stressed the importance of having a strong set of rules for the entire US, they said ISPs are already subject to a “patchwork” of state laws.

FCC officials today said the reclassification of broadband will close a national security “loophole.” They said the FCC relies on its authority over voice service to keep hostile foreign actors from compromising networks and that regulating broadband under Title II will provide additional power to impose cybersecurity requirements on network operators. That includes blocking authorizations of companies controlled by adversarial governments, they said.

More than just net neutrality

Rosenworcel stressed that placing broadband under Title II classification will give the FCC stronger authority over more than just net neutrality. For example, the FCC can use Title II to require Internet providers to address long outages and report detailed data on outages, she said.

The FCC fact sheet said Rosenworcel’s plan will let the agency “enhance the resiliency of broadband networks and bolster efforts to require providers to notify the FCC and consumers of Internet outages.”

Rosenworcel also pointed to the 2018 incident in which Verizon throttled a fire department’s “unlimited” data during California wildfires. “As a result of the Title II repeal, the FCC didn’t have any authority to intervene and fix it,” Rosenworcel said.

Rosenworcel said that because FCC authority is generally centered on phone systems instead of broadband, the commission often needs “duct tape and baling wire” to provide legal justification for its rules. Among other things, Title II would give the FCC stronger authority to fight robotexts in the same way it fights robocalls, she said.

Title II also has benefits for broadband providers, like giving cable companies rights to attach wires to telephone poles, she said. The FCC’s Title II repeal “eliminated the pole-attachment rights of broadband-only providers,” she said.

FCC’s Title II powers

Net neutrality proposals always trigger debate over whether the FCC has authority to impose rules governing how broadband providers treat Internet traffic. The Obama-era rules crafted under Wheeler survived a court appeal in 2016, affirming the FCC’s authority to regulate broadband providers as common carriers under Title II of the Communications Act.

In 2019, Pai’s repeal of those rules survived a court challenge for similar reasons—judges said the FCC has authority to decide whether broadband should or shouldn’t be regulated under common carrier rules.

To be regulated under common carrier rules, broadband access must be classified as a telecommunications service rather than as an information service. One appeals court judge called Pai’s claim that broadband isn’t a telecommunications service “unhinged from the realities of modern broadband service,” but the federal appeals court said the FCC has broad authority to classify broadband as either an information service or telecommunications as long as it provides a reasonable justification for its decision.

The FCC is not proposing to re-impose broadband privacy rules that were eliminated by Congress in 2017. Those privacy rules were also based on the FCC’s Title II authority, but the Republican-led Congress used its review power to kill the rules and to prohibit the FCC from issuing similar regulations in the future.

While that Congressional decision limits the FCC’s rule-making authority on privacy, FCC officials said today that reclassifying broadband will ensure that ISPs won’t be allowed to sell customers’ location data. Phone companies are already prohibited from selling location data, and Rosenworcel probed mobile carriers’ use of geolocation data last year.

Industry pins hopes on 2022 SCOTUS ruling

This time around, at least some of the debate will center on a 2022 Supreme Court ruling in a case involving the Environmental Protection Agency, which emphasized that agencies must point to “clear congressional authorization” when making decisions on “major questions.”

Two former Obama administration solicitors general, Donald Verrilli, Jr. and Ian Heath Gershengorn, argued in a white paper this month that under the “[Supreme] Court’s current doctrine, the issue of reclassification of broadband under Title II is a ‘major question.’ And, the Commission lacks the ‘clear congressional authorization’ that the Court requires.”

However, the white paper was funded by two of the most active opponents of net neutrality rules—the industry trade groups USTelecom and NCTA–The Internet & Television Association, which represent broadband companies like AT&T, Verizon, Comcast, and Charter. Those groups sued the Obama-era FCC in an attempt to overturn the net neutrality rules years before the EPA ruling, making similar claims that the FCC lacked authority to regulate broadband as a common carrier service.

Verrilli and Gershengorn are both partners at law firms and said in their white paper that “over the course of our careers, we have represented the federal government and broadband providers on issues relevant to this paper.”

Question over “major questions”

Harold Feld, a longtime telecom lawyer who is senior VP at consumer-advocacy group Public Knowledge, argued last year that the Supreme Court’s EPA decision likely won’t prevent the FCC from imposing net neutrality rules. Feld wrote that the EPA ruling relied on the Gonzales v. Oregon decision, “which cites the FCC’s authority over broadband in Brand X approvingly as an example of where Congressional delegation is ‘clear.'”

Of course, no one can predict with absolute certainty whether the FCC will win if the Supreme Court takes up the case. “It all depends on what the Court means by a ‘major question’ that requires ‘clear proof’ that Congress intended to vest the agency with the power to do the thing,” Feld wrote.

Today, FCC officials said they’re confident in the legality of the planned reclassification because the commission has been classifying broadband under the Communications Act since the 1990s, and each reclassification has been upheld in court.

Another complicating factor is that the FCC would shift to Republican control if President Biden is unable to win re-election in November 2024. A Republican-controlled FCC could reverse Rosenworcel’s decision or choose not to put up much of a fight in court if it’s challenged.

FCC Republican Brendan Carr issued a statement today blasting what he called “the Biden Administration’s unnecessary and unlawful plan for exerting government control over the Internet.” Carr said the FCC should heed the Verrilli/Gershengorn analysis but didn’t mention the white paper’s industry funding.

Jon Brodkin has been a reporter for Ars Technica since 2011 and covers a wide array of telecom and tech policy topics. Jon graduated from Boston University with a degree in journalism and has been a full-time journalist for over 20 years.

This article was published on September 26, 2023 at arstechnica.