By Suzanne Bearne

Up until three years ago, PR and advertising firm boss Marian Ventura was more than happy to work on projects for oil and gas companies.

“I felt I was pushing change from the inside, collaborating to enhance their transparency and accountability,” says the founder of Done!, which is based in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

She says that in Latin America the fossil fuels industry is considered “prestigious”. “They sponsor every sustainability event or prize in the region, and of course they are the ‘best clients to have, for their big budgets.”

Then in 2019, Ms Ventura’s feelings started to shift when she decided to certify her business as a so-called “B Corp” organization. This is a global certification scheme whereby firms aim to meet the best possible social and environmental standards.

“As a B company, we know that in order to fulfill our corporate purpose we cannot turn a blind eye to these questions: Who am I selling to? What am I selling? Will I be proud of what I am selling in 10 years?,” says Ms Ventura.

As a result, she started to reduce her oil clients, but in 2021 she went one step further.

Last year, she decided that Done! would become one of the now 350 advertising and PR firms who have joined a movement called Clean Creatives. Joining the movement means they pledge to refuse any future work for fossil fuel firms, or their trade associations.

“We dropped off at least four active clients related to oil and gas, and refused a dozen quotation requests, that actually keep coming,” says Ms Ventura.

She adds that her decision has come in for criticism. “People with whom we have stronger relationships, told me that they don’t agree with our position, because they believe oil and gas are irreplaceable resources for society, and they assure it can be developed in a responsible way.”

The United Nations (UN) recognizes that the burning of fossil fuels – oil, natural gas and coal – “are by far the largest contributor to climate change”. It says that they account for “nearly 90% of all carbon dioxide emissions”.

Speaking on the subject back in April, the UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres said “some government and business leaders are saying one thing, but doing another”. He added: “High‑emitting governments and corporations are not just turning a blind eye, they are adding fuel to the flames.”

Meanwhile, a report this year by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change said that “corporate advertisement and brand building strategies may also attempt to deflect corporate responsibility”. The study went on to ask whether tighter advertising regulation was required.

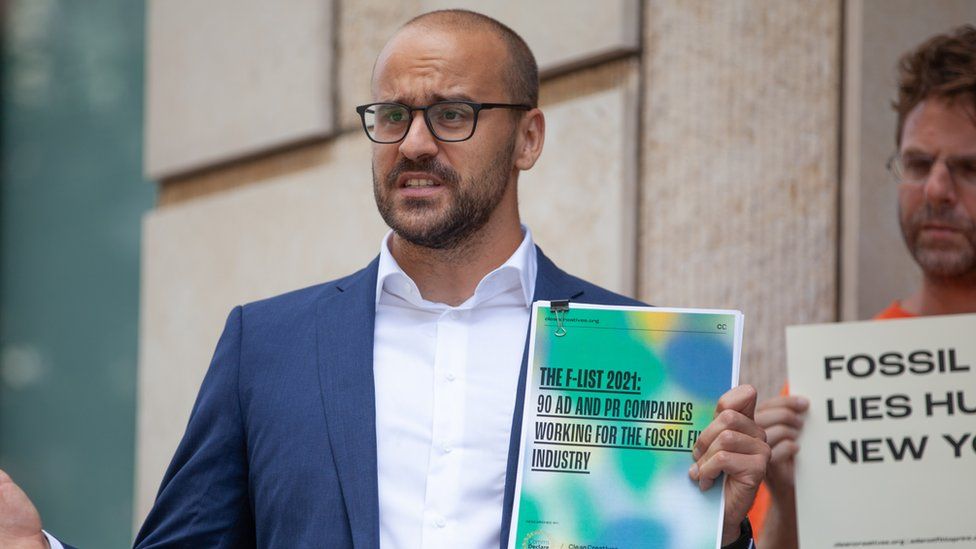

Duncan Meisel, director at US-based Clean Creatives, says he sees a shift happening. “We know there’s agencies not taking the pledge who have told us privately that they are no longer pitching to fossil fuel clients. It’s a step forward.”

He adds: “The fossil fuel industry uses advertising agencies and PR agencies to make it harder for governments to hold them accountable. And ads are misleading and make companies seem more committed to climate action than they really are.”

Some advertising firms are, however, continuing with fossil fuel clients, such as the UK’s WPP, whose subsidiaries have worked with the likes of BP, Shell and Exxon Mobile.

“Our clients have an important role to play in the transition to a low carbon economy and how they communicate their actions must be accurate,” says a WPP spokesman. “We apply rigorous standards to the content we produce for our clients, and seek to fairly represent their environmental commitments and investments.

“We will not take on any client, or work, whose objective is to frustrate the policies required by the Paris Agreement [on climate change].”

Meanwhile, the world’s largest PR firm Edelman, was at the end of last year criticized for its work for fossil fuel companies. Its clients have included the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers, and also Exxon Mobile.

The US headquartered firm subsequently carried out a 60-day review of its climate strategy, and boss Richard Edelman said in a company blog post in January that it might have to “part ways” with clients not committed to net zero emissions.

Edelman declined to give a subsequent comment to BBC News for this article.

Oil and gas trade association, Offshore Energies UK (OEUK), says it is wrong to criticize PR and advertising firms that work with the energy sector.

“Pressuring agencies to avoid working with companies involved oil and gas is counter-productive to combating climate change, as they’re also the ones with the decades of energy expertise that are developing and rolling out the cleaner technologies that are needed,” says OEUK external relations director, Jenny Stanning.

New Economy is a new series exploring how businesses, trade, economies and working life are changing fast.

A spokesperson for the Advertising Association says that it does not believe the fossil fuel industry should be banned from advertising “but we do recognize the right for individual companies to decide who they do and don’t work with”.

“Accuracy and honesty in all advertising is paramount,” he adds. “This is an area carefully regulated by both the CMA [Competition and Markets Authority] and ASA [Advertising Standards Authority], which expects advertisers to be able to show evidence for any claims they make on the environmental impact of the products and services they feature.

“We believe in the freedom of speech, and Clean Creatives are exercising that right. Our end goals are the same i.e. net zero, but we think a more nuanced approach is required.”

Solitaire Townsend, boss of UK advertising agency and PR firm Futerra, gave up working with oil and gas clients some 15 years ago.

She says that more and more firms in her industry will have to follow suit – if they wish to attract the best staff.

“A lot of agencies will come to the point where they have to make the decision if they want to be able to recruit the brightest,” says Ms Townsend. “The young ones don’t want to work with oil and gas [clients].”

Suzanne Bearne is a business reporter for BBC News.

This article was published on July 28, 2022, at BBC News.