By Micha Narberhaus

By Micha Narberhaus

The Broken Stories of Mainstream Activism

To this day, few civil society organisations are promoting the much-needed transition to a new economic system based on the principles of ecological limits, solidarity, human well-being, and intergenerational justice, nor are many organisations embracing the complexity of systemic change in their strategies, campaigns, and projects.

Many activists realise that the ways their organisations (or civil society sector) are trying to fix these problems don’t seem to work anymore. They believe that while they have won many battles, we as humanity are losing the planet; while the world would be worse off without the battles that have been won, in the end things are not improving but only getting less bad than they would have been without these actions. These activists and change agents have the energy to do something about it—and want to try new ways—but lack the resources and the support.

The frustrations that these civil society change agents are experiencing are resulting from the collapse of long-held beliefs about who they are and how they as activists can bring about change in the world. These are what we call broken civil society stories:

Our economy is capable of developing the technological solutions that can and will ultimately solve our ecological and humanitarian crises. This story is broken. We are ourselves so deeply entrenched in the western worldview based on deep beliefs in the positive forces of technological progress and economic growth that we can’t see that this worldview and the system themselves are the root cause of current crises and that the system is not given by nature and not set in stone. Instead, it is a social construction that we can and must change, but it will require a process of changing worldviews.

We have to work towards what is possible instead of what is needed. This story is broken because, although there are many advantages and it seems less risky to be pragmatic rather than utopian, too much pragmatism and tactics reinforce the unsustainable status quo. Only if activists shift their actions much more towards what is needed and allow for utopia to be part of our strategy will activism have a chance to shift the logic of the debate. The space for what is possible will then shift over time.

Policy advocacy and lobbyism are the best way to be influential. This story is broken because, although it can’t be denied that civil society has an impact in the political game, the margins ultimately are very small and even what looks like a big success very often in the long run doesn’t really change much. The institutions themselves are failing, so playing the game through the institutional processes cannot achieve system change.

We need to raise more funds and lobby for more aid budgets for the global south to develop and eradicate poverty. This story is broken because the messages that most CSOs still send through their fundraising campaigns are as successful as they are harmful in perpetuating false stereotypes and hiding the real causes of poverty. The whole logic of the aid industry is still based on a hierarchy relationship between donors and recipients, far from the idea of a relationship of solidarity.

We are the experts on our issue, so we should focus on concrete feasible proposals to improve the issues. This story is broken because, given the systemic and complex nature of so many of today’s problems, the responses of silo work are often inadequate. Only a multi-issue perspective makes it completely obvious that we have to tackle the deeper economic and cultural root causes instead of proposing technical fixes.

The world is divided between the good and the bad. We are on the good side, and to achieve social change, we have to fight the bad. This is a broken story because the systemic problems of our times are not mainly the fault of one group or another. Instead, there is one main enemy; it is the system. The systemic shift that is needed requires changes at many different levels. Whilst the abuse of power by certain privileged groups resisting systemic change without doubt requires more and better organised protests and fights, the main task we have to confront is one of collective realisation that we all have to change and give up some of our deep beliefs and habits and to embark on a process of searching and finding the new societal and economic models. In other words, the ‘99% vs. 1%’ Occupy slogan was very useful in highlighting the dramatic increase in global inequality. But it is misleading in that the fight for system change is not one of the 99% against the 1%. It omits the fact that the growing global consumer classes and those aspiring to become part of them are resisting change almost as much as the 1%.

An Emerging New Story of Systemic Change

Activists and civil society change agents from all over the world are increasingly starting to realise that the climate crisis, the inequality crisis, and many other issues so close to activists’ hearts will not come anywhere near getting resolved if we do not change the economic system. Within all diversity of movements like the Commons, de-growth, Great Transition, or the solidarity economy, within and around them a new story of systemic change is emerging:

- We can build an economic system that provides sufficient material well-being to be equitably shared by nine billion people while leaving sufficient resources for future generations. A happier and better society will emerge from a refocus away from material and economic wealth to spiritual and social wealth.

- Cooperation and collaboration are as natural to humans as is competition. In an economy that focuses much more on humans’ predisposition and will to collaborate, humans and the planet will thrive. A redefined concept of freedom is the right of all humans and future generations to equitably share the resources of our planet.

- While we still need to pursue the opportunities of more efficient and environmentally friendly technologies, we need to focus much more on the root causes of environmental destruction and support a cultural and economic transformation away from today’s consumerism and narrow-minded national economic interest.

- As humanity and planetary citizens, together we have to take care of the earth’s resources and distribute them fairly, leaving a rich planet for future generations. We will create a rich and thriving global community if we share our abundant and our scarce commons. Our lives will be enriched if we hold multiple levels of identity (local, regional, and planetary).

- While historic inequalities and injustices require more economic transfers from rich countries to poorer countries and support in using the resources in a meaningful way, the main focus in our fight for global justice and sustainability is to collaborate with change agents across the planet to create the foundations and the cultural shift that bring us on a path towards an eco-solidarity economy based on the commons as a structural principle.

- If civil society concentrates on and lives the values it wants to see in the world, it can be an example for and a leading actor in a cultural transformation towards planetary solidarity, cooperation, and simpler living.

- If civil society across its sectors learns how to unite forces for a deeper transformation of the current political and economic institutions, it can tackle much more effectively the multiple urgent crises we are facing.

How Can Activists Learn to Support Systemic Change?

Campaigns designed for systemic change need to have a longterm perspective and cannot define their success by some specific short-term policy outputs. Furthermore, they need to focus on changing the logic of the debate by pointing at the root causes of the problems rather than the symptoms. Finally, they need to help by mobilising and speaking to people in many different parts of society, not only to those who are most affected or marginalised. The civil rights movement in the US or the anti-slavery movement were successful when they were supported by people who were themselves white or not slaves, respectively.

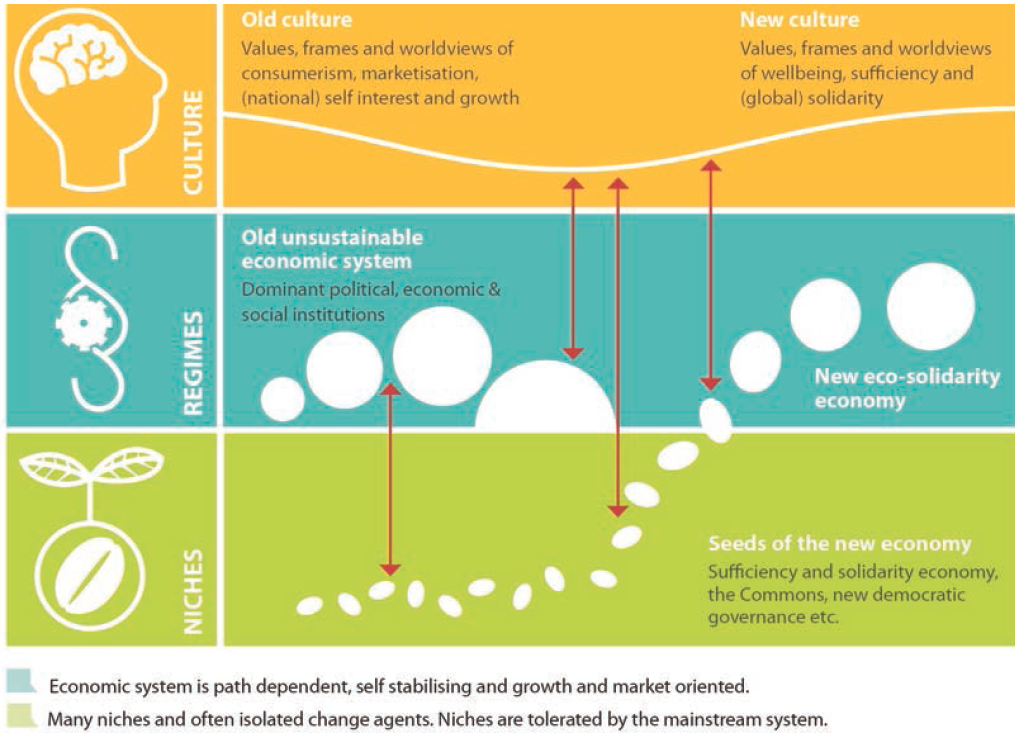

The multi-level model (see diagram) has proven to be of practical relevance to help activists have an informed discussion on how they can develop a new type of campaign designed for system change. It is an evolved version of the multi-level-perspective diagram previously used and developed by transition researchers Frank Geels, Jan Rotmans, Adrian Smith, and others.i

The model’s purpose is primarily to help activists develop, refine, and improve their theories of change when designing system change strategies and campaigns. In other words, it is about learning what different aspects and levels of change have to be taken into account and how activists have to change the way they work if they want to become successful change agents for a post-growth economy.

Multi-Level Model: A Systemic Transition to a Post-Growth Economy

The model works at three levels:

- Culture: This level is where the current cultural values, frames, and worldviews lie, which are currently dominated by consumerism, marketization, nationalism, and self-interest. Here a shift to a culture of sufficiency, well-being, and solidarity has to emerge to support the transition to the new economy.

- Regimes: This level is where the dominant political, economic, and social institutions of the old unsustainable economic system lie and where—to succeed in the transition—the institutions of the de-growth economy have to consolidate.

- Niches: This level represents the protected spaces where the seeds of the new system emerge and are experimented with, and where the most promising innovations become stronger and get sufficient support to eventually institutionalise.

The model is based on the understanding that all three levels are important for a transition to the new economic system. Each of the levels holds important core messages to be aware of:

- Culture: Activists, organisations, and campaigns need to embody the values of the new system to support the transition. The current reality is that they are still too often communicating and representing the values of self-interest, consumerism, and growth, and are contributing to perpetuate the current culture.

- Regimes: Institutions are highly path-dependent, self-stabilising, and generally rejecting a fundamental transformation. While successful in promoting incremental changes, much of the current policy advocacy work of civil society organisations is (or will be) ineffective at promoting systemic change. By playing the political game, these institutions cannot expect to make effective contributions to change.

- Niches: While there are a growing number of experiments with alternative economic models, these are normally either tolerated by mainstream institutions or co-opted by the system to play by the market rules. In many civil society organisations, there is a lack of understanding of the emerging radical system innovations and insufficient belief in one’s own potential to support them. Civil society needs to find ways to connect, strengthen, and illuminate the pioneers of the new system, thus increasing the potential that the seeds of the new economy become systems of influence.

Professional organisations should be much more strategically engaged and in support of the emerging and existing movements that can play a role in and become coherent voices for systemic change. Many more cross-sectorial platforms of deep learning and strategising about how to support the Great Transition are required.

The main value of the model becomes apparent when we examine it as a whole and explore the existing and potential feedback loops between the three change levels. Here the main message is that for a successful transition to a de-growth economy strong positive feedback loops between all levels will be required. The transition will require strong impulses from a cultural shift and a strengthening of the niches to create a virtuous circle of feedback loops to eventually unlock the institutional lock-ins at the regimes level. The reverse message is that the model loses most of its value if we interpret it in a simplistic way—for example, by classifying any given civil society strategy or approach into one of the three levels without evaluating what core message the change level holds and what feedback loops it might create, support, or weaken.

To conclude, the multi-level model can help activists to assess their current strategies against their potential to encourage (or hinder) a systemic transition. It can also support strategic conversations about possible new system change strategies and how they could eventually mutually reinforce each other.

While the model is a useful and flexible tool for strategic conversations, it is not an all-explaining wonder box. It has to be populated little by little with knowledge and wisdom from theory and practice to improve understanding about more effective activism for systemic change.

For civil society to become a decisive actor towards a transition to a new economic system, many more activists and change agents are needed for this journey. The game has to be raised to grow and spread the seeds of new civil society that is emerging.

i See Smart CSOs Report: Effective Change Strategies for the Great Transition (p.15ff)Φ

Micha Narberhaus is the founder of the Smart CSOs Lab (www.smart-csos.org). Micha has an academic background in economics and an earlier career in the private sector. Since 2004 he has worked at the interface between research and civil society activism with a deep interest in theories of change, systems thinking, and interdisciplinary approaches. This article appeared in the Winter quarterly publication of Kosmos, journal for global transformation, and may be found here.