By Mark Rudd

An organizer of the 1968 Columbia University protests, Mark Rudd analyzes why the message against war, then and now, is the same.

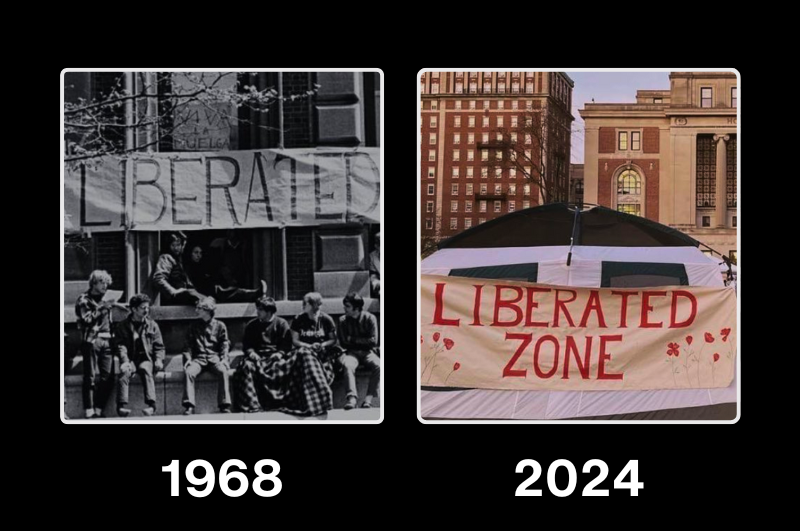

On the left, students occupying the Mathematics Hall in April 1968. On the right, a tent from the 2024 student encampment.

What is the ethical response to witnessing a great moral crime? Turn away and allow oneself to be distracted? Pretend it doesn’t exist? Or acknowledge the crime for what it is, and take some sort of action to try to stop it?

Students at Columbia in 1968 understood that our own government — with the complicity of our university — had invaded Vietnam in order to wage a war of occupation against a civilian population, committing mass murder with tactics like carpet bombing of whole provinces, spraying chemical poisons on rice fields and forcing entire rural populations into concentration camps. What’s more, we knew that the mostly white university, against community opposition, was expanding into one of the few parks in neighboring Harlem. Black Columbia students in particular — having grown up during the postwar civil rights era — felt the imperative to act.

As the chairman of the Columbia chapter of Students for a Democratic Society, I helped organize campus-wide protests that spring, during which hundreds of students occupied five buildings — a traditional nonviolent tactic. The occupation was followed by a mass strike that closed Columbia for more than a month.

Now, over half a century later, Columbia students are once again engaging in consciously nonviolent tactics to protest the university’s complicity in a war — this time Israel’s invasion of Gaza, which has caused the deaths of more than 34,000 human beings, mostly women and children, and displaced 2.3 million.

After setting up tents on a patch of lawn and facing severe scrutiny in the media as well as arrests and suspensions, another group began occupying one of the same halls we occupied in 1968. Just as we were, the students are sick at heart and feel compelled to stop a moral obscenity.

All the rest is commentary.

Then and now

What the protesters are telling the country, then and now, is that it’s not morally acceptable for a university to conduct secret research in support of the war against Vietnam or to invest in Israeli military industries. Defending the status quo, the leadership of the institution and their funders naturally try to shut the students up.

Back in 1968, Columbia’s administration called on New York City cops to empty the buildings, badly beating and arresting almost 700 students. Fifty-six years to the day later, the NYPD were again called in to break up a student occupation, arresting around a hundred students as they cleared the occupied hall and encampment last night. It was the second time in the last month — since her trip to Washington, D.C., where she pledged loyalty and obeisance to far-right politicians in a bid to save her job — that Columbia’s president brought police on campus to make arrests.

Despite the similarities between then and now, there are differences.

Most of the leadership of the Columbia strike in 1968 was young men like myself. That no longer appears to be the case — either at Columbia or the other university protests around the country.

In 1968 we made the mistake of answering the police violence with anger, fighting them and calling them pigs. We blurred the line between nonviolence (the occupation of buildings) and violence (our slogans and rhetoric), thereby undercutting our moral position.

The students protesting the slaughter in Gaza, with their diverse leadership are making no such mistakes. They are thoroughly nonviolent. There may be individuals or provocateurs who defy the strategy, but at least the protesters are trying to make their intention clear. In a little-reported Instagram post last week entitled “Columbia’s Gaza Student Protest Community Values,” they wrote “At universities across the nation our movement is united in valuing every human life” and “We firmly reject any form of hate or bigotry.” Setting up tents and praying for the souls of the dead, all the dead, is not violence.

The charge of antisemitism

Having myself been raised, like most American Jews, to believe that my Jewish identity is entwined with Israel, I understand why criticism of Israel feels threatening. Generational trauma is bred into us.

Yet, having moved to an anti-Zionist position because of Israel’s brutality and racism toward the Palestinian people, I have been labeled a “self-hating Jew,” a “traitor” and worse. Now a new epithet has appeared, the “unJew.”

No matter: Those of us who reject hatred, violence and denial of human and civil rights — and view that as intrinsic to Jewish identity — still remain Jews. Concerned for the well-being and future of the seven million Jews living in Israel, we advocate for (as do many nonviolent Palestinians) a future democratic Israel/Palestine, where all citizens are equal, close to the ideal of a truly democratic United States so many of us are struggling for. The longer this war continues, the further off this solution or any other becomes — and the more dangerous the situation gets for Jews in Israel. Is this war against Gaza good for the Jews?

Pretending to defend Jews who feel threatened by criticism of Israel, the far right (which harbors true antisemites in their ranks) — Nazis, Proud Boys and even a deranged person who murdered 11 at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh — have been quick on the attack. Speaker of the House and MAGA acolyte Mike Johnson last week shed crocodile tears at Columbia, working himself up about the supposed antisemitism on campus.

If he were serious about suppressing such hatred, he would disavow and suppress the lie at the heart of both his white Christian nationalist movement and the anti-immigration movement: that “the Jews” are conspiring to create the flood of non-white immigration in order to “replace” white people.

The fascist media, of course, have jumped to attack the protesters. The liberal media, always worried about the rise of antisemitism, follows.

Courage and clarity

Buried in this blizzard of accusations is the protesters’ original point, that mass slaughter is happening right now in Gaza.

Despite threats of violence, expulsion, arrest, doxxing and being barred from future employment by the antisemitic label, the Gaza protesters aren’t backing down. Their ranks are increasing, with more than 40 campuses across the country holding protests, and more than 1,200 students arrested. Let’s hope that this incipient movement grows to stop American support for the war against Gaza — and to eventually rectify one-sided American policy toward Israel.

No matter how hard we Americans are fed the lie that war is peace, many young people can see through it. They should be cherished and respected for their moral clarity and courage.

Mark Rudd was chairman of the Columbia chapter of Students for a Democratic Society in April, 1968. Subsequently he became a “National Traveler” for SDS and was elected the last National Secretary of SDS in June, 1969. Because of his delusions about revolution in this country he and his clique, “Weatherman,” closed down SDS, the largest radical student organization, at the height of the war, to his eternal shame. He was one of the founders of the ill-conceived and ill-fated Weather Underground in 1970. A federal fugitive until 1977, he suffered no consequences due to the government’s illegalities. Since then he has been a full-time organizer and community college instructor in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He is the author of the memoir Underground, My Life in SDS and Weatherman. He is also a student of organizing, especially nonviolent strategy.

This article was published on May 1, 2024 at wagingnonviolence.